Architecture and Concepts

Introduction

SirixDB is an evolutionary, (bi)temporal, tamper-proof append-only database system and event store that never overwrites data. Every time you commit a transaction, SirixDB creates a new lightweight snapshot. It uses a log-structured copy-on-write approach, whereas versioning takes place at the page and node level. Let’s first define what a temporal database system is all about.

A temporal database is capable of retrieving past states. Typically, it stores the transaction time when a transaction commits data. If the valid time is also stored, when a fact is true in the real world, we have a bitemporal relation: two time-axes.

SirixDB can help answer questions such as the following: Give me last month’s history of the Dollar-Pound Euro exchange rate. What was the customer’s address on July 12th, 2015, as it was recorded back in the day? Did they move, or did someone correct an error? Did we have errors in the database, which were corrected later on?

Let’s turn our focus toward the question of why historical data has not been retained in the past. We postulate that new storage advances in recent years present possibilities to build sophisticated solutions to help answer those questions without the hurdle state-of-the-art systems bring.

Advantages and disadvantages of flash drives, for instance, SSDs

As Marc Kramis points out in his paper “Growing Persistent Trees into the 21st Century”:

The switch to flash drives keenly motivates to shift from the “current state” paradigm towards remembering the evolutionary steps leading to this state.

The main insight is that flash drives such as SSDs, which are common nowadays, have zero seek time while unable to do in-place data modifications. Flash drives are organized into pages and blocks. Due to their characteristics, they can read data on a fine-granular page level but only erase data at the coarser block level. Furthermore, blocks first have to be erased before they can be updated. Thus, whenever a flash drive updates data, it is written to another place. A garbage collector marks the data, which has been rewritten to the new place as erased at the previous block location. The flash drive can store new data in the future at the former location. Metadata to find the data at the new location is updated.

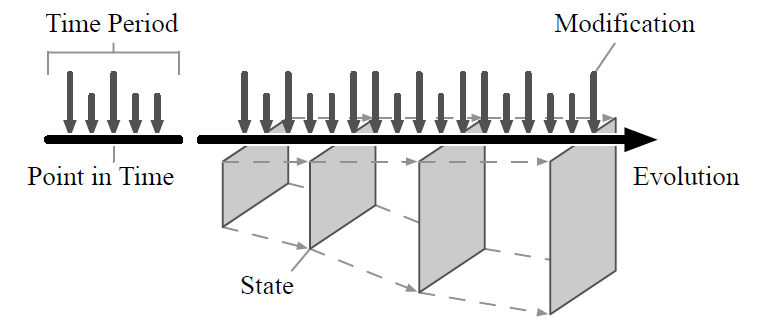

Evolution of state through fine-grained modifications

The next figure from Marc Kramis describes the evolution of state over time through fine grained modifications

Furthermore, Marc points out that those small modifications usually involve writing the modified data and all other records on the modified page. This is an undesired effect. Traditional spinning disks require clustering due to slow random reads of traditionally mechanical disk head seek times.

Instead, from a storage point of view, it is desirable only to store the changes. As we’ll see, it boils down to a trade-off between read and write performance. On the one hand, a page must be reconstructed in memory from scattered incremental changes. On the other hand, a storage system has to store more records than necessarily have changed to fast-track the reconstruction of pages in memory.

How we built an Open Source storage system based on these observations from scratch

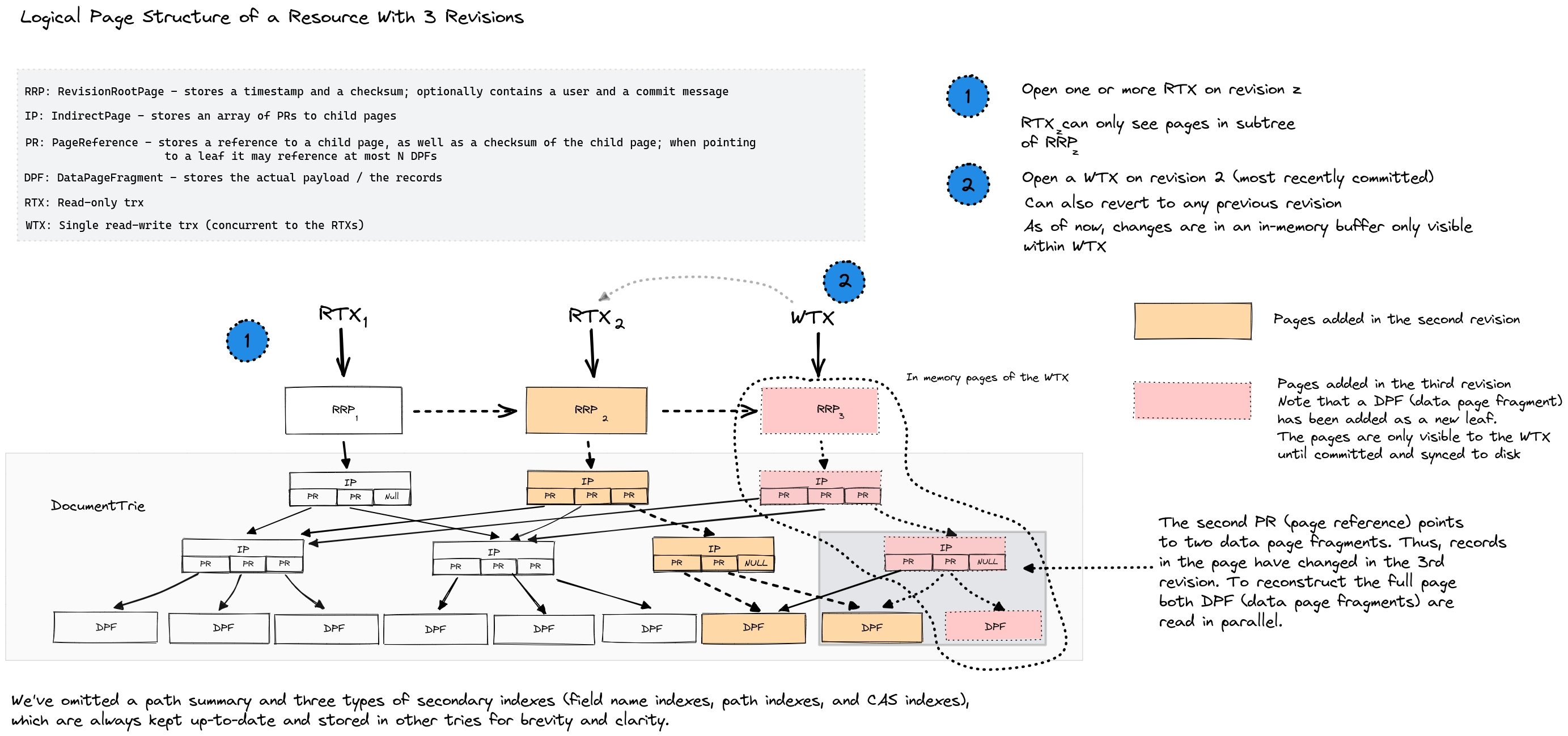

SirixDB stores data in resources (the equivalent of relations/tables in relational database systems) within databases. A resource session allows starting a single read-write transaction per resource bound to the most recent revision. It’s also possible to revert to any past state, whereas modifications and changes to the past revision, once committed, create a new revision. All revisions between the past revision and the former most recent revision are still available. In addition to the single read-write transaction, a resource session allows to begin N-concurrent read-only transactions bound to any revision (per default, the most recent revision). Thus, no other locks are used except for a single read-write trx lock. Instead of revision numbers, SirixDB also allows starting the transaction bound to a specific revision by a given timestamp. Logically the storage manager searches via binary search on a sorted array of timestamps for the first revision, closest to the given timestamp and greater. Optionally a commit can store who’s committed the trx and created the new revision and an optional commit message.

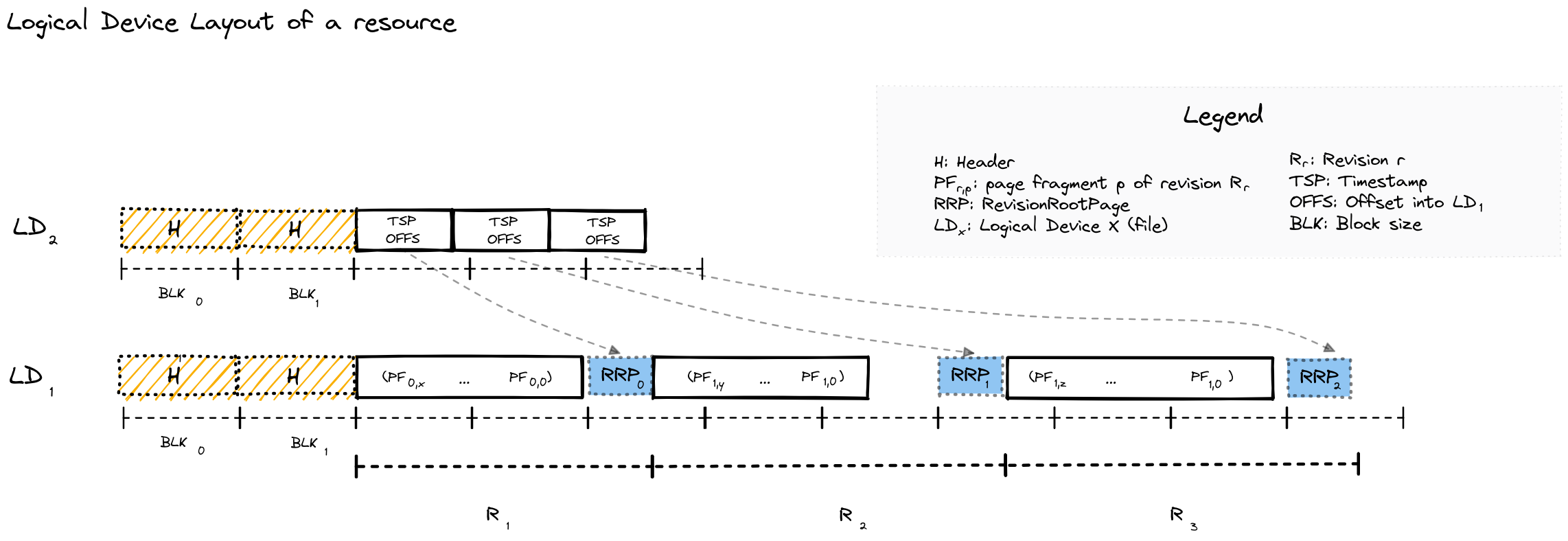

SirixDB stores per revision and page deltas. Due to the zero seek time of flash drives, SirixDB does not have to cluster data. It only ever clusters data during transaction commits. Data is written sequentially to log-structured storage. It is never modified in place.

Database pages are copied to memory, updated, and synced to a file in batches. When a transaction commits, SirixDB flushes pages to persistent storage during a postorder traversal of the internal tree structure.

The page structure is heavily inspired by the operating system ZFS. We used some of the ideas to store and version data on a sub-file level. We’ll see that Marc Kramis developed a novel sliding snapshot algorithm to version data pages based on observed shortcomings of versioning approaches from backup systems.

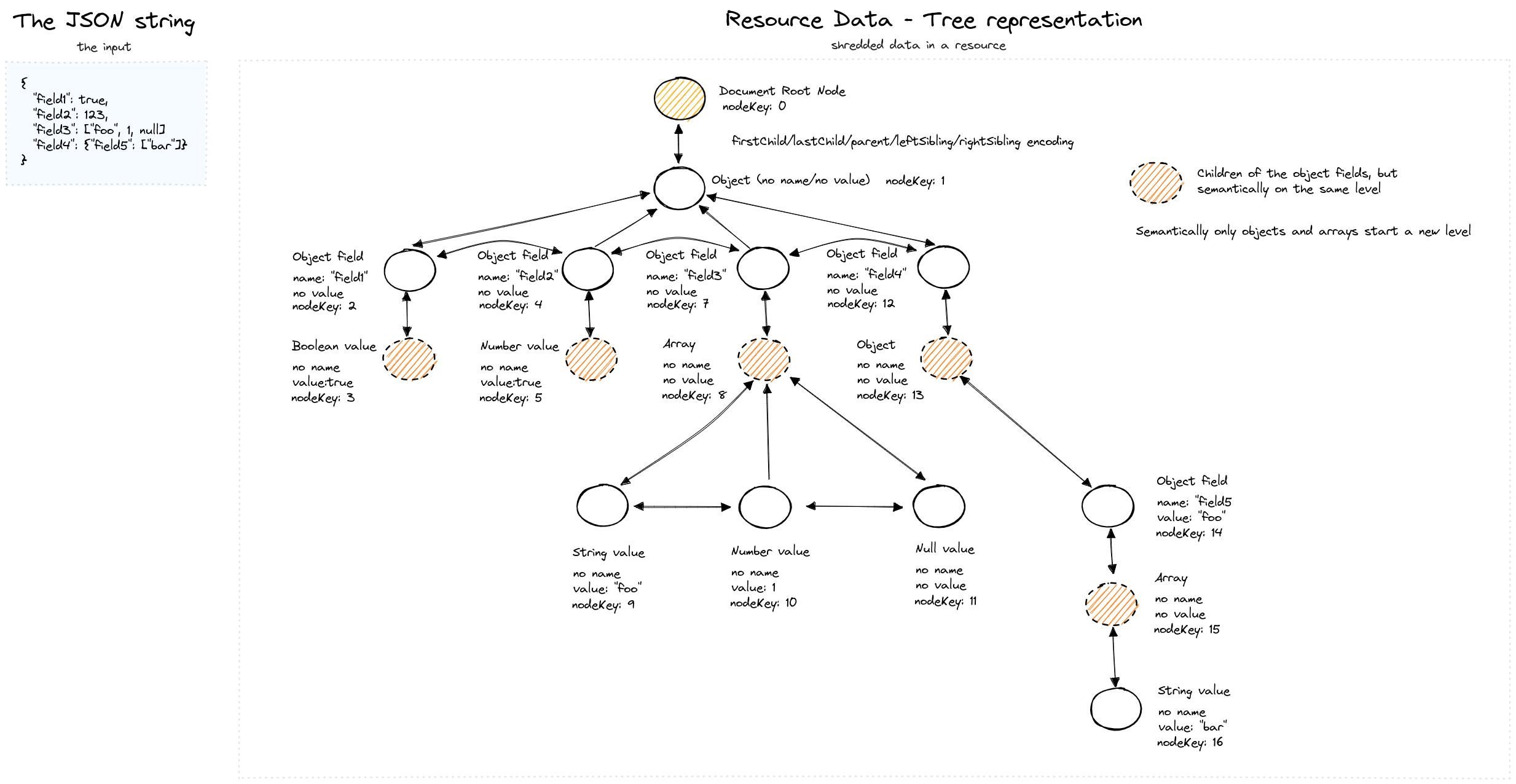

Tree-structure

SirixDB stores databases, that is, collections of resources. Resources are the equivalent unit to relations/tables in relational database systems. A resource typically is a JSON or XML file stored in SirixDBs binary tree-encoding. The following figure depicts constructing a JSON tree by parsing the input JSON string and creating fine-grained nodes.

We’ve omitted several details here for brevity. Still, a simple dictionary compression ensures that object field names are only stored once in an in-memory map ((re-)constructed from a keyed trie) and referenced through a 32-bit integer from the node. Similarly, as we’ll see in a bit, path summary nodes/path class records are referenced from the nodes and stored in another trie.

Optionally, the storage manager also computes a rolling hash when inserting/updating/deleting nodes, adapting all ancestor hashes. When using the REST-API, this is especially important for a lightweight optimistical concurrency control system. Each GET request results in a response with an ETag-Header with the new hash set as the value. A subsequent request might be an update to the node (by sending the previously received hash value in the request). If the subtree has been modified concurrently and in parallel by another user, the hashes won’t match, and the operation fails/the transaction is aborted. TODO: figure. The hashes are also crucial to speed up an ID-based diffing algorithm, which computes a set of diff operations. Also optionally, however, trading space and time for fast change tracking between revisions, SirixDB records the changes in small JSON files in a specific format, which includes the anchor node, the type of change, the changed nodes, and optionally metadata.

Each node and revision in SirixDB is referenced by a unique, stable identifier, which never changes. A simple sequence generator assigns monotonically increasing 64-bit node IDs. Neighbour nodes are referenced through their IDs, as well as the first- and last child and the parent. Thus, the node encoding is based on a local encoding.

Secondary index types

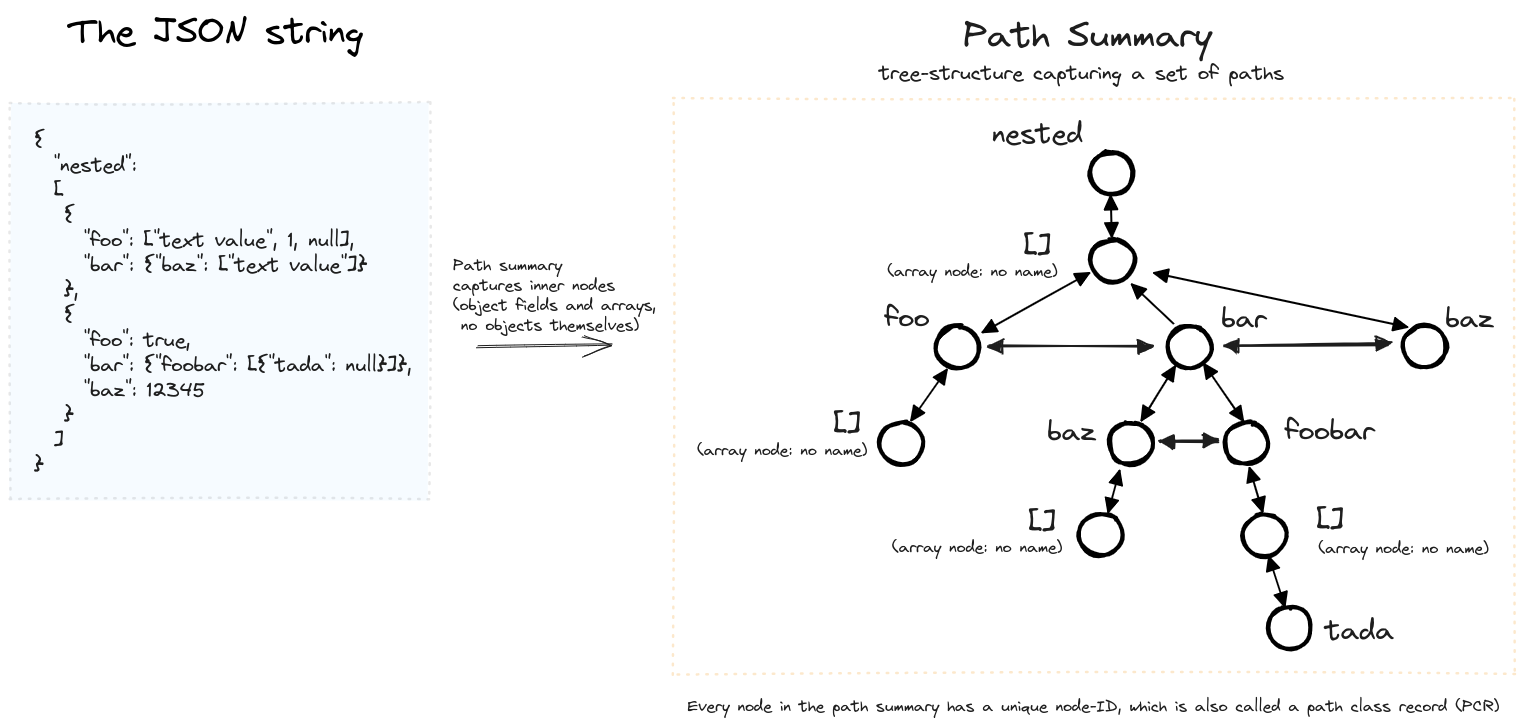

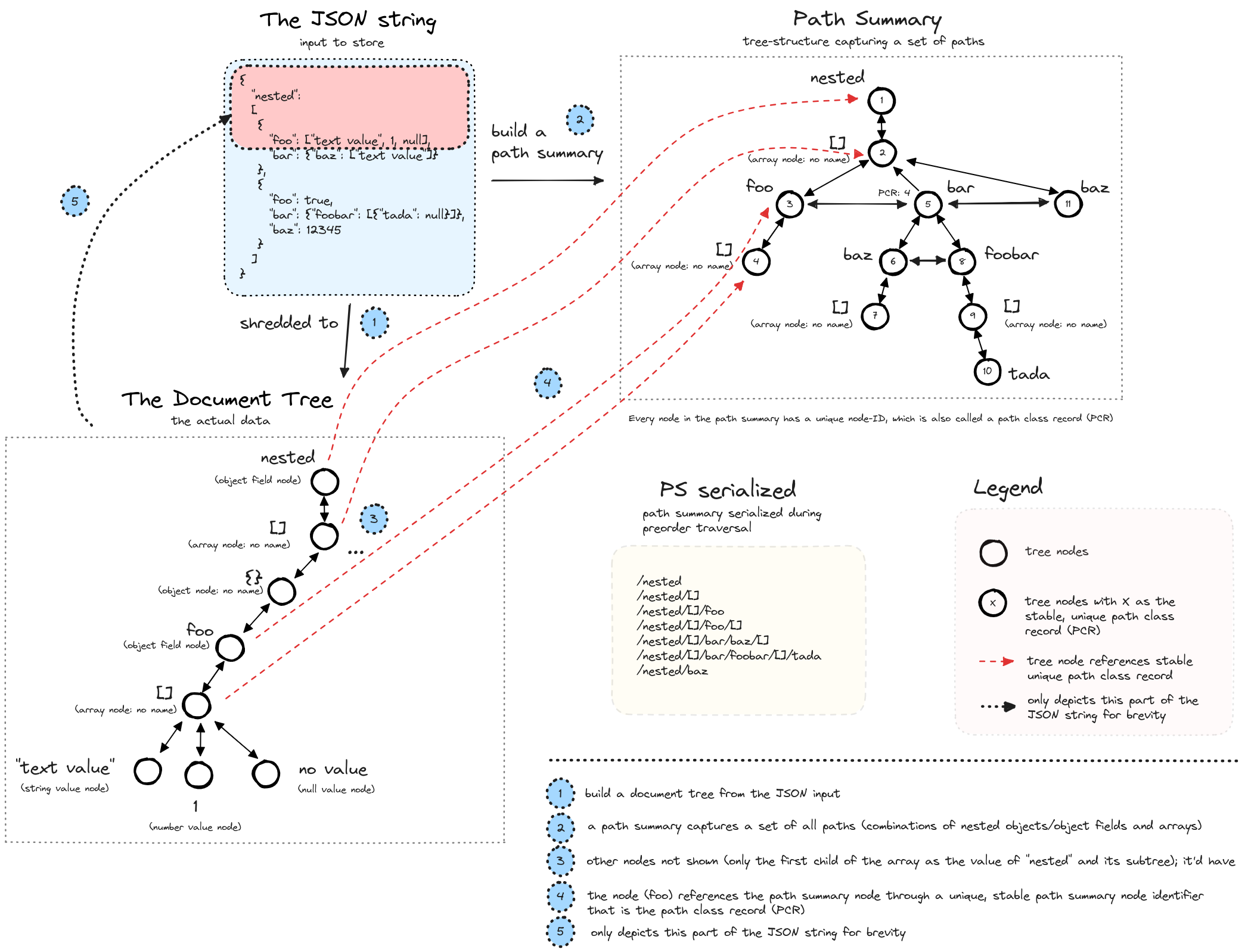

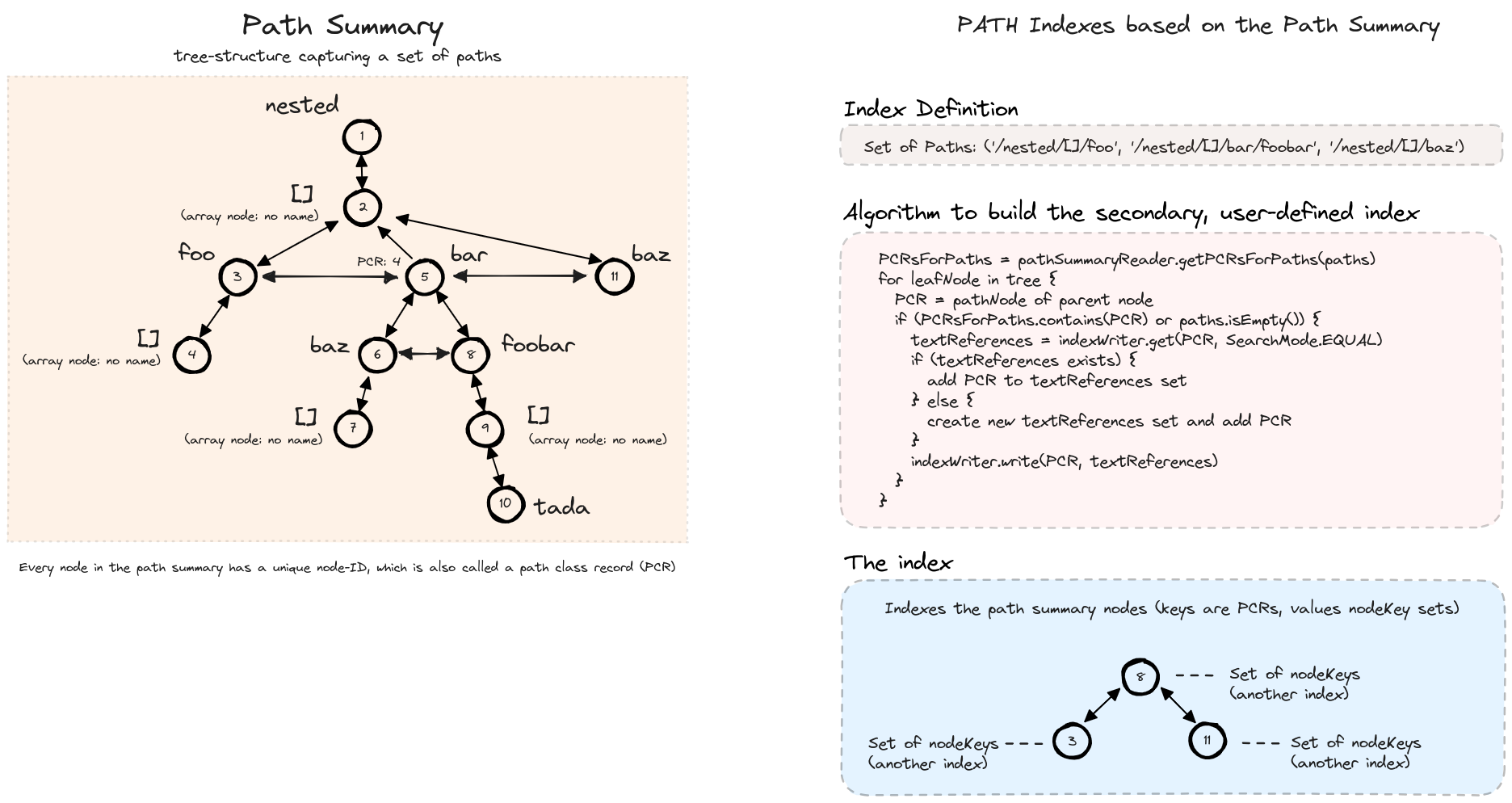

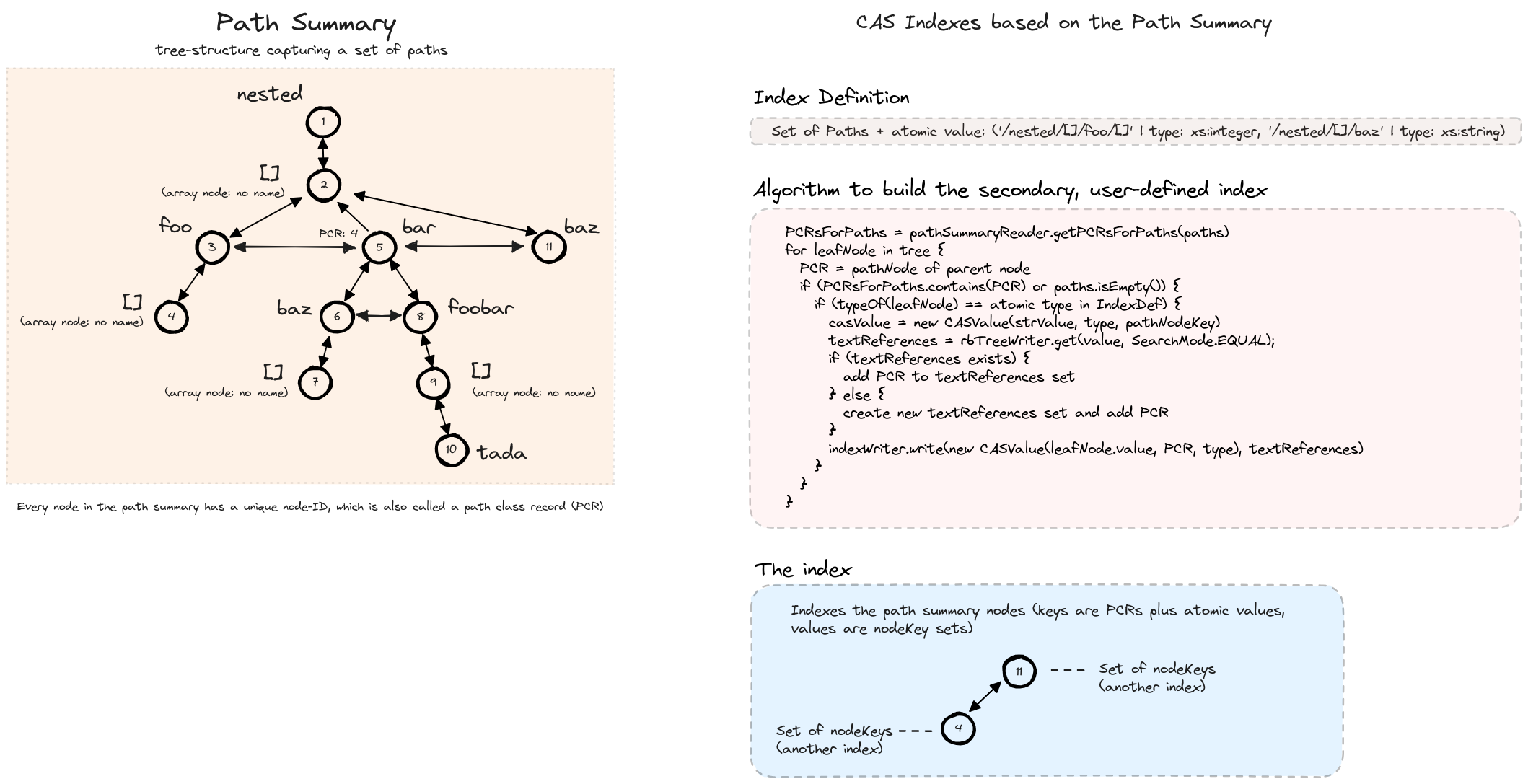

SirixDB stores a small in-memory path summary, a set of all paths in the resource (stored in a tree structure). The paths are not ordered. The individual nodes in the path summary are also referenced through unique, stable 64-bit node IDs, so-called path class references. The path summary is crucial for user-defined path indexes on individual paths and for so-called cas (content-and-structure) indexes, which index both typed values and the path to the root.

The storage engine stores three types of indexes: Name/field indexes, path indexes, and cas indexes.

Name/field indexes are trivial. They store node keys for the given names in an index, which resembles indexing columns in relational database systems.

It keeps the indexes at all times up-to-date. Furthermore, it stores the indexes and the actual data in dedicated tries. As such, they are part of a read-write transaction and versioned. The following diagram shows a path summary built for a given JSON input. It is built along with the actual data, the JSON tree.

The next diagram depicts the relationship between the actual data, the stored JSON tree, and the path summary. Each inner node references the corresponding path node key/path class reference (PCR).

The path summary is crucial for index selectivity. That is fine-grained, user-defined indexes on individual paths. It ensures that indexes can be adjusted to document characteristics, query workload, and maintenance overhead. Moreover, selective indexes reduce update costs, compared to indexes covering all paths. The next diagram depicts a simple algorithm to build path indexes. As the path summary is small, it’s kept in memory, and access to individual nodes is cheap due to a map (path class reference <=> path node). The path class references matching a given path are cached. Individual path class references are recomputed on demand whenever a new path node with a given name is inserted.

The most selective type of index in SirixDB is a user-defined, typed, content-and-structure (CAS) index. In addition to individual paths, typed values are stored in the indexes. Thus, whenever potential index matches are searched for leaf value nodes, matching PCRs are based on the parent paths of the object field value nodes. Furthermore, non-matching types are not indexed.

Transaction commit and persistent data structures

All data structures are stored in log-structured persistent tries. Whenever updates are made (e.g., a node is inserted), the path to a revision root page is copied, and a new chain of pages is appended to a data storage file. The nodes themselves are stored in leaf node pages of keyed tries. Instead of copying the whole leaf node pages, however, SirixDB supports a clever new algorithm called sliding snapshot. The following figure depicts the main document index: a trie, which stores the nodes based on their 64-bit node keys. Each commit creates a new revision root page with a monotonically increasing revision number and, as said, a chain of ancestor pages starting with a copy of a leaf node page.

We assume that a read-write transaction modifies a record in the leftmost DataPageFragment, a leaf node page of the trie. Depending on the versioning algorithm SirixDB uses, the modified nodes and probably some other nodes in the page are copied to a new page fragment. First, SirixDB stores all changes in an in-memory transaction (intent) log only visible to the write trx. Second, during a transaction commit, the page structure of the new RevisionRootPage is serialized in a postorder traversal and appended to a data file.

We’ve borrowed ideas from the Adaptive Radix Tree (ART) and Hash Array Mapped Tries (HAMT) to compress inner pages (IndirectPages) with a lot of null references (currently in our system the rightmost IndirectPages, which are the inner nodes of the tries). The IndirectPages thus might be based on storing only four references, a bitmap page or a full page, currently.

All changed DataPageFragments are written to persistent storage, starting with the leftmost. If other changed data pages exist underneath an inner node page of the trie (IndirectPage), SirixDB serializes these before the IndirectPage, which points to the updated data pages. Then the IndirectPage, which points to the updated revision root page, is written. The indirect pages are written with updated references to the new persistent locations of the data pages.

SirixDB also stores checksums in the parent pointers as in ZFS. Thus, the storage engine in the future will be able to detect data corruption and heal itself once we partition and replicate the data. SirixDB serializes the whole page structure in this manner. We also intend to store an encryption key in the references to support encryption at rest.

SirixDB must update the ancestor path of each changed RecordPage/DataPageFragment. However, storing indirect pages is cheap. Each reference is left unchanged, not pointing to a new page or page fragment. Thus, unchanged pages (not on the ancestor path of changed pages) are referenced at their respective position in the previous revision and never copied or rewritten.

Versioning at the page-level

One of the most distinctive features of SirixDB is that it versions the RecordPages. It doesn’t merely copy all records of the page, even if a transaction only modifies a single record. The new data page fragment always contains a reference to the previous version. Thus, the versioning algorithms can dereference a fixed predefined number of page fragments at maximum to reconstruct a RecordPage in memory.

A sliding snapshot algorithm used to version data pages can avoid read and write peaks. The algorithm avoids intermittent full-page snapshots needed during incremental or differential page-versioning to fast-track its reconstruction.

Versioning algorithms for storing and retrieving page snapshots

SirixDB stores, at most, a fixed number of nodes. That is the data per database page (currently limited to 1024 nodes). The nodes themselves are of variable size. Overlong records, which exceed a predefined length in bytes, are stored in additional overflow pages. SirixDB stores references to these pages in the data pages.

SirixDB implements several versioning strategies best known from backup systems for copy-on-write operations of data pages. Namely, it either copies

- the full data page, that is, any node in the page (full)

- only the changed nodes in a data page regarding the former version (incremental)

- only the changed nodes in a data page since a full-page dump (differential)

Incremental versioning is one extreme. Write performance is best, as it stores the optimum (only changed records). On the other hand, reconstructing a page needs intermittent full snapshots of pages. Otherwise, performance deteriorates with each new page revision as increments increase with each new version.

Differential-versioning tries to balance reads and writes better but is still not optimal. A system implementing a differential versioning strategy has to write all changed records since a past full dump of the page. Thus, only two revisions of the page fragment must be read to reconstruct a data page. However, write performance also deteriorates with each new revision of the page.

Write peaks occur during incremental versioning due to the requirement of intermittent full dumps of the page. Differential versioning also suffers from a similar problem. Without an intermittent full dump, a differential versioning system has to duplicate vast amounts of data during each new write.

Marc Kramis developed a novel sliding snapshot algorithm, which balances read/write performance to circumvent any write-peaks.

The algorithm makes use of a sliding window. First, any changed record must be written during a commit. Second, any record older than a predefined length N of the window that has not been changed during these N-revisions must be written, too. Only these N-revisions at max have to be read. Fetching of the page fragments can be done in parallel or linear. In the latter case, the page fragments are read starting with the most recent revision. The algorithm stops once the full page has been reconstructed. You can find the best high-level overview of the algorithm in Marc’s Thesis: Evolutionary Tree-Structured Storage: Concepts, Interfaces, and Applications